Whence the origins of instrumentally accompanied solo song, from which the whole world of present-day popular music can, by whatever meandering route, trace its descent? To be sure, busy instrumentalists are to be observed in the pictorial evidence of antiquity and the medieval period, but the extent to which they served to accompany human voices remains unknowable. Not until around the comparatively recent year of 1600, when the music of this concert began to be composed and arranged, does the accompanying role of instruments begin to take shape in the historical record.

In England, two unexpected outcomes of Tudor religious reform were that young choristers formerly employed in the singing of numerous daily church services were instead instructed in viol playing, and marshalled into troupes of boy actors. The incidental music for the dramas thus staged quickly took the form of what are now known as consort songs, in which four instruments accompany the unchanged voice of a boy soloist. Beyond their dramatic function, such songs were set to poetry of many kinds, and in households where the budget did not stretch to a quartet of viols their accompaniments were instead sung, or condensed for lighter instrumentation. In the latter manner we hear the consort song ‘O death, rock me asleep’, with words that—although now popularly attributed to Anne Boleyn on the eve of her execution on 19 May 1536—remain just as anonymous as the music to which they are set.

While from 1600 viol ensembles gained popularity as a medium of domestic music-making, as dramatic instruments they soon gave way to the lute, a much more convenient solo instrument on which a skilled singing actor could serve as his own accompanist. Owing to the lute’s capacity for playing arrangements as well as original compositions, and to the intermittent availability of extended vocal and instrumental resources, the English stage songs of the period typically have such knotty version histories that a definitive arrangement or instrumentation may not be said to exist. A case in point is the song ‘Have you seen but a bright lily grow’, which accompanies an extra-marital seduction in Act II of Ben Jonson’s 1616 comedy The Divell is an Asse. The music, believed to be the work of Shakespeare’s theatre lutenist Robert Johnson, survives in two versions with bass-only accompaniment for viol (one plain, the other decorated) and a third with a fully chordal lute part.

Similarly, it seems that John Dowland, when sharing one of his hundred or so lute solos, never jotted it down the same way twice. No picking or choosing is necessary with the ‘Fancy’ numbered 5 in Diana Poulton’s modern catalogue, for this item survives only in a single manuscript. In contrast, the Lachrimae Pavan exists in probably more versions, arrangements, variations and tribute compositions than any other work from the period, one being Dowland’s own song adaptation ‘Flow, my tears’. It was with a warning about ‘false and unperfect’ copies that—fortunately for posterity—he published the (presumably original) solo lute version in 1596.

Although in 1612 Dowland was to publish a song bearing the dedication ‘to my loving Country-man Mr. John Forster the younger, Merchant of Dublin in Ireland’, there exists not a shred of evidence to substantiate the claim of the maverick Irish music historian William H. Grattan-Flood that the composer was born at Dalkey, Co. Dublin. In fact the earliest known details of his biography concern four years spent at Paris, around the age of twenty, in the service of England’s ambassador to the French court Sir Henry Cobham. Whatever rancour it may have caused him, Dowland’s failure in 1594 to secure a position as lutenist to Queen Elizabeth I was to lead to his becoming England’s most highly reputed musician in Europe. By invitation, he took up appointments at the Saxon and royal Danish courts, and his compositions circulated widely in continental prints and manuscripts.

On returning to England in 1606, Dowland joined a circle of musicians that encompassed all the contemporaneous composers represented in this programme. From 1612, in possession at last of his long hoped-for court preferment, he served with Robert Johnson and the English-born Alfonso Ferrabosco among King James I’s private lutenists. Ferrabosco went on to collaborate with the Huguenot descendent Nicholas Lanier on music for the Masque of Augurs (1622), and was later to marry into the Lanier family. Following the accession of Charles I in 1625, Lanier (wearing his alternative hat of art-dealer to the new king) sojourned at Venice, and very likely made Monteverdi’s acquaintance there (if, indeed, he had not already done so on a prior visit in 1610). And in 1648, John Jenkins composed an elegy for Henry Lawes’s brother William, who had died fighting for King Charles, and who as a young man had transcribed compositions by Ferrabosco and written variations on them.

None of these musicians could escape the influence of Italy on their art-form, and all of them more or less embraced it. Whether or not the Florentine and Venetian exponents of the new genre of monody truly believed they had recreated the music of ancient Greek drama, the resulting declamatory style—of which the lighter side is epitomised by Monteverdi’s ‘Ohimè ch'io cado’ of 1624—was to make its mark on the English song repertory of the whole seventeenth century. Prior to the Civil Wars, much of that repertory arose from what might be described as the Stuart equivalent of today’s West-End musical, the court masque. Having developed from the masked ball, this new brand of entertainment became increasingly lavish at the hands of librettist Ben Jonson and set designer Inigo Jones. It was to Jonson’s words that Ferrabosco composed ‘So beauty on the waters stood’ for the 1608 Masque of Beauty, which he went on to publish the following year in his first and only printed song book.

With conspicuous success, England took Italy’s lead also in aspects of musical form and execution. In the sixteenth century, the importation of stock bass lines used by Italian minstrels for improvising dance music had given rise to the English term ‘ground bass’, or simply ‘ground’. The use of such basses in seventeenth-century Italian opera, typically for laments in minor keys and slow triple time, engendered some of the finest products of solo English vocal music. These ground-bass songs could range in mood from the reflective tranquility of Lanier’s posthumously published setting of Thomas Carew’s poem ‘No more shall meads be deck’d with flowers’ to the desolation of Purcell’s ‘O let me weep’, the plaint with which the character of Juno opens Act V of the 1692 theatre masque The Fairy Queen.

The English excelled too in the Italian art of extempore instrumental elaboration, notably set down in Riccardo Rognoni’s 1592 textbook Passaggi per potersi essercitare nel diminuire terminatamente con ogni sorte di instromenti (passages enabling the comprehensive practising of diminution on all kinds of instruments). At the end of the volume are notated four possible treatments of Cipriano Rore’s famous 1547 madrigal ‘Anchor che col partire io mi sento morire’ (Although parting from you seems to me like dying). Though it would not appear until 1659, the principal English textbook on the same subject—Christopher Simpson’s The Division-Violist—has taken its place among the most important seventeenth-century writings on music. Certain copies of Simpson’s book survive with manuscript additions of divisions by his friend Jenkins, among whose output of more than 800 instrumental pieces are more than twenty examples of the genre.

Whereas prior to the Civil Wars all public performing—be it for religious or dramatic purposes—remained strictly the preserve of boys and men, the eighteen-year closure of the theatres during the wars and Interregnum banished English song culture to the private domain, where at last the repertory could safely be interpreted also by women. This significant development, which anticipated the swift appearance of professional actresses on the Restoration stage, is instantiated by Henry Lawes in words dedicating his 1655 Second Booke of Ayres to Mary Harvey (Lady Dering): ‘those songs which fill this book have received much lustre by your excellent performances of them’. No Reprieve, the second song in this collection (and one of more than 400 in the composer’s œuvre), sets melodramatic words by Lawes’s co-Royalist Sir John Berkenhead. (The apostrophised Lucasia, whose name derives from the heroine of William Cartwright’s 1635 tragicomedy The Lady Errant, was a pet-name for Berkenhead’s fellow poet and reputed Platonic lover, Anne Owen.)

The musical privations of the Commonwealth era, to which Lawes’s 1655 preface alludes, are reflected in his songs’ sparse texturing for voice and instrumental bass, a far cry from the rich five-part consort songs of the preceding century. Although written amid the greater opulence that ensued from the Restoration of the monarchy, Purcell’s nearly 150 domestic songs are mostly characterised by the same economical format. In such items as ‘Celia’s fond’ and ‘She loves and she confesses too’, accompanists must complete the harmony idiomatically from the bass part without specific guidance from the composer. In contrast, Purcell’s French contemporaries the celebrated singing teacher Michel Lambert (in his more than 300 airs sérieux) and the organist-composer Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (in his two dozen cantatas) scrupulously annotated their bass parts to enable on-the-fly harmonisation without reference to the parts for voice and obbligato instruments.

by Andrew Johnstone

spenser

2023

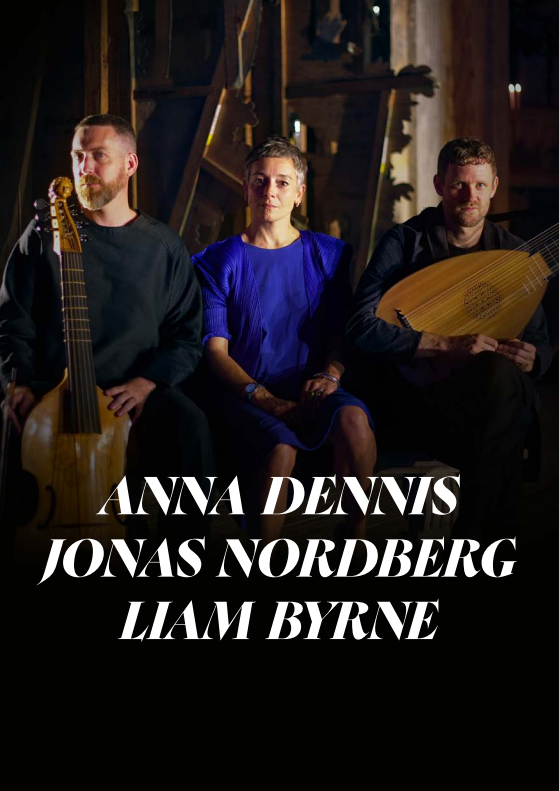

Written for Anna Dennis, Jonas Nordberg and Liam Byrne, spenser is a ‘portrait’ of the 16th Century Elizabethan court poet Edmund Spenser (1553-99), which continues my ongoing interest in the concept of musical portraiture. The writer and art critic John Berger posits the idea that portraiture betrays as much, if not more, about the artist themself – the way they see the world, their physical, aesthetic, social, and political perspective – as it does about the subject of the portrait. In this sense, it can be a method to shape an understanding of oneself through the exploration of someone else.

Widely considered perhaps the greatest poet of the English Renaissance, Spenser is known for his technical achievements (the ‘Spenserian stanza’) across an array of sonnets, odes and allegorical works, including, most famously, The Fairie Queene.

He was also an English state servant and went to Ireland in 1580 where he acquired land in the Munster plantation and served under Lord Grey and Walter Raleigh in the Second Desmond Rebellion. His opinions on Ireland and the Irish found expression in his prose pamphlet A View of the Present State of Irelande. Written as a dialogue between two Englishmen, it calls for the pacification of the Irish through scorched earth policies (the effectiveness of which he’d witnessed during the Desmond Rebellion) as well as the erasure of the Irish language.

As a portrait, spenser is concerned with the complexities of the man and his image: simultaneously the great Elizabethan poet and militant reformer – someone who can articulate, with succinct beauty, how language gives expression to the very being of a people, while simultaneously advocating for the destruction of it. Alongside rhymes of my own composition it makes use of extracts from the poet’s own writings (including A View, as well as the marriage ode Epithalamion) as the basis for a collage of texts, all set within a fractured structure of sharply juxtaposed moods and tempi.

David Coonan

Anna Dennis, Jonas Nordberg and Liam Byrne will be touring to Galway, Dublin, Westmeath, Donegal, Kilkenny and Waterford from 22 — 30 November 202